“Bob Marley has died!” I exclaimed. Having switched on the car radio before starting the engine, one of Marley’s songs was playing on John Peel’s ‘BBC Radio One’ ten-to-midnight show. I knew immediately what that meant. Peel was a long-time reggae fan, though I had not heard him play a Marley track for years. There was no need to await Peel’s voice announcing the sad news. I had read that Marley was ill but had not understood the terminal gravity of his health.

Peterlee town centre was dark and desolate at that late hour. I had walked to my little Datsun car across a dark, empty car park adjacent to the office block of Peterlee Development Corporation, accompanied by my girlfriend who was employed there on a one-year government job creation scheme. We had attended a poetry reading organised by Peterlee Community Arts in the building, an event she had learnt of from her marketing work. It was my first poetry reading. Only around a dozen of us were present, everyone else at least twice our age. But what we heard was no ordinary poetry.

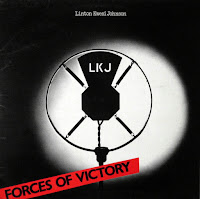

Linton Kwesi Johnson had coined his work ‘dub poetry’ in 1976 and already published three anthologies and four vinyl albums, voicing his experiences as a Jamaican whose parents had migrated to Britain in 1962. Peterlee new town seemed an unlikely venue for a ‘dub poet’, a deprived coal mining region with no discernible black population, but working class Tyneside poet Keith Armstrong had organised this event as part of his community work there to foster residents’ creative writing. Johnson read some of his excellent poems and answered the group’s polite questions. It was an intimate, quiet evening of reflection.

Due to my enthusiasm for reggae, I was familiar with Johnson’s record albums as one strand of the outpouring of diverse innovation that Britain’s homegrown reggae artists had been pioneering since the early 1970’s. Alongside ‘dub poetry’ (poems set to reggae), there was ‘lovers rock’ (soulful reggae with love themes sung mostly by teenage girls), UK ‘roots reggae’ (documenting the Black British experience) and a distinctly British version of ‘dub’ (radical mixes using studio effects). One name that was playing a significant writing/producing role spanning all these sub-genres was Dennis Bovell, alias ‘Blackbeard’, of the British group ‘Matumbi’. His monumental contributions to British reggae are too often understated.

Until then, there had been plenty of reggae produced in British studios and released by UK record labels such as ‘Melodisc’, ‘Pama’ and ‘Trojan’, but most efforts had been either a rather clunky imitation of Jamaican reggae (for example, Millie’s 1964 UK hit ‘My Boy Lollipop’ [Fontana TE 17425]) or performed by ‘dinner & dance’-style UK groups such as ‘The Marvels’. I admit to having neglected Matumbi upon hearing their initial 1973 releases, cover versions of ‘Kool & The Gang’s ‘Funky Stuff’ [Horse HOSS 39] and ‘Hot Chocolate’s ‘Brother Louie' [GG 4540]. It was not until their 1976 song ‘After Tonight’ [Safari SF 1112] and the self-released 12-inch single ‘Music In The Air’/’Guide Us’ [Matumbi Music Corp MA 0004] that my interest was piqued as a result of the group’s creative ability to seamlessly bridge the ‘lovers rock’, ‘roots reggae’ and ‘dub’ styles. Both sides of the latter disc remain one of my favourite UK reggae recordings (sadly, these particular mixes have not been reissued).

In 1978, Matumbi performed at Dunelm House and, after attending the gig, it was my responsibility as deputy president of Durham Students’ Union to sit in my office with the band, counting out the cash to pay their contracted fee. They were on tour to promote their first album ‘Seven Seals’ self-produced for multinational ‘EMI Records’ [Harvest SHSP 4090]. It included new mixes of the aforementioned 12-inch single plus their theme for BBC television drama ‘Empire Road’, the first UK series to be written, acted and directed predominantly by black artists. Sensing my interest in reggae, the group invited me to join them for an after-gig chat, so I drove to their motel several miles down South Road and we sat in its bar for a thoroughly enjoyable few hours discussing music.

As part of my manic obsession with the nascent ‘dub’ reggae genre, I had bought albums between 1976 and 1978 credited to ‘4th Street Orchestra’ entitled ‘Ah Who Seh? Go Deh!’ [Rama RM 001], ‘Leggo! Ah Fi We Dis’ [Rama RM 002], ‘Yuh Learn!’ [Rama RMLP 006] and ‘Scientific Higher Ranking Dubb’ [sic, Rama RM 004]. They were sold in blank white sleeves with handwritten marker-pen titles and red, gold and green record labels to make them look similar to Jamaican-pressed dub albums of that era. However, it was self-evident that most tracks were dub mixes of existing UK recordings by Matumbi backing various performers, engineered and produced by Bovell for licensing to small UK labels. I also had bought and worn two of their little lapel badges, one inscribed ‘AH WHO SEH?’, the other ‘GO DEH!’, from a London record stall. During our conversation in the bar, Bovell expressed surprise that I owned these limited-pressing albums, and even more surprise that I recognised Matumbi as behind them. They remain prime examples of UK dub.

It was Bovell who had produced Linton Kwesi Johnson’s albums, and it was Matumbi who had provided the music. Alongside a young generation of British roots reggae bands such as ‘Aswad’ and ‘Steel Pulse’, Johnson’s poetry similarly tackled contemporary social and political issues with direct, straightforward commentaries. It was a new style of British reggae, an echo of recordings by American collective ‘The Last Poets’ whose conscious poems/raps had been set to music (sometimes by ‘Kool & The Gang’) since 1970, and whose couplets had occasionally been integrated into recordings by Jamaican DJ ‘Big Youth’ in the 1970’s. Of course, MC’s (‘Masters of Ceremonies’) had been talking over (‘toasting’) records at ‘dances’ in Jamaica since the 1960’s, proof that the evolution of ‘rap’ owed as much to the island’s sound system culture as it did to 1970’s New York house parties.

In Peterlee, Johnson read his poems to the audience without music, his usual performance style. It was fascinating to hear his words without any accompaniment. For me, the dub version of Johnson’s shocking 1979 poem ‘Sonny’s Lettah’ (retitled ‘Iron Bar Dub’ on ‘LKJ In Dub’ [Island ILPS 9650]) is brilliantly effective precisely when the music is mixed out to leave his line “Me couldn’t stand up there and do nothin’” hanging in silence. Sadly, memories of Johnson’s performance that night were suddenly eclipsed by the news of Marley’s death. I drove the eight miles to our Sherburn Village home in stunned silence. I was sad and shocked. It was only then that his sudden loss made me realise how much Marley had meant to me.

Despite having listened to reggae since the late 1960’s, I admittedly arrived late to Bob Marley’s music. Though I had heard many of his singles previously, it was not until his 1974 album ‘Natty Dread’ [Island ILPS 9281] that I understood his genius. At that time, I was feeling under a lot of personal pressure which I tried to relieve by listening to this record every day for the next two years. At home, my father had run off, leaving our family in grave financial difficulties. At school, I was struggling with its inflexibility, not permitted to take two mathematics A-levels, not allowed to mix arts and science A-levels, not encouraged to apply to Cambridge University. Back in my first year at that school, I had been awarded three school prizes. However, once my parents separated and then divorced, I was never given a further prize and the headmaster’s comments in my termly school reports became strangely negative, regardless of my results.

Feeling increasingly like an unwanted ‘outsider’ at grammar school, Marley’s lyrics connected with me and helped keep my head above encroaching waters rising in both my home and school lives. I knew I was struggling and needed encouragement from some source, any source, to continue. For me, that came from Marley’s music. While my classmates were mostly listening to ‘progressive rock’ albums with zany song titles (such as Genesis’ ‘I Know What I Like In Your Wardrobe’), I was absorbed by reggae and soul music that spoke about the daily struggle to merely survive the tribulations of life. After ‘Natty Dread’, I rushed out to buy every new Marley release.

During the months following Marley’s death, I was absorbed by sadness. It felt like the ‘final straw’. The previous year, I had landed a ‘dream job’, my first permanent employment, overhauling the music playlist for 'Metro Radio'. Then, after successfully turning around that station’s fortunes, I had unexpectedly been made redundant. I was now unemployed and my every job application had been rejected. That experience had followed four years at Durham University which had turned out to be a wholly inappropriate choice as it was colonised by 90%+ of students having arrived from private schools funded by posh families. I felt like ‘a fish out of water’. I loved studying, I loved learning, I desired a fulfilling academic life at university … but it had proven nigh on impossible at Durham.

This is where I want to be

But I know that this will never be mine”

Months later, my girlfriend awoke one morning and told me matter-of-factly that she was going to move out and live alone. She offered no explanation. We had neither disagreed nor argued. We had been sharing a room for three years, initially as students in a horribly austere miners’ cottage in Meadowfield whose rooms had no electrical sockets, requiring cables to be run from each room’s centre ceiling light-fitment. Now we were in a better rented cottage in Sherburn, though it had no phone, no gas and no television. Her bombshell announcement could not have come at a more vulnerable time for me. I had already felt rejected by most of my university peers and then by my first employer. At school previously, I had passed the Cambridge University entrance exam but had been rejected by every college. At Durham, I had stood for election as editor of the student newspaper, but its posh incumbent had recommended a rival with less journalistic experience. A decade earlier, my father had deserted me and his family, and now the person I loved the most had done the same.

I just could not seem to navigate a successful path amidst the world of middle- and upper-class contemporaries into which I had been unwittingly thrown, first at grammar school, then at Durham, and now in my personal life too. Most of those years, I felt that circumstances had forced me to focus on nothing more than survival, whilst my privileged contemporaries seemed able to pursue and fulfil their ambitions with considerable ease. I had to remind myself that I had been born in a council house and had attended state schools, initially on a council estate. My girlfriend had not. I had imagined such differences mattered not in modern Britain. I had believed that any ‘socio-economic’ gap between us could be bridged by a mutual feeling called ‘love’. I now began to wonder if I had been mistaken. I felt very much marooned and alone. My twenty-three-year-old life was in tatters.

Fast forward to 1984. I had still not secured a further job in radio. I was invited to Liverpool for a weekend stay in my former girlfriend’s flat. We visited the cathedral and attended a performance at the Everyman Theatre. It felt awkward. I never saw her again. It had taken me months to get over the impact of Bob Marley’s death. It took me considerably longer to get over my girlfriend ending our relationship.

But looking back over my shoulder

You’re happy without me”

No comments:

Post a Comment