Nazi soldiers were everywhere. Battalions of Nazis marching down wide boulevards. Nazis standing on convoys of tanks, waving flags. Row upon row of Nazis saluting speeches by their leader. Nazis fighting on battlefields. It was exhausting to watch for too long and nothing like 'Indiana Jones'. In fact, it was a little bit frightening.

I had viewed so many hours of ‘MTV’ that I knew Stina Nordenstam’s song ‘Little Star’ by heart. Seeking alternative entertainment, I manually retuned the hotel room’s television and was shocked to discover a grainy black-and-white channel that was broadcasting Nazi propaganda twenty-four hours a day. I was like Dennis Quaid in the movie ‘Frequency’, pulling signals from the ether transmitted several decades earlier. This bizarre television service must have been a sideshow of the civil war raging on European soil only a hundred miles from my present location, atop a Budapest hill 479 metres above sea level.

My life under ‘hotel arrest’ was proving extremely tedious. To be accurate, I could leave any time I wished but my accommodation was hardly ‘Hotel California’. I was stranded alone, five miles from the city centre in countryside popular for walking holidays in summer but dead as a dodo mid-winter. No buses, no taxis, no shops, no mobile phone, no laptop, no internet access. It felt like sensory deprivation to be cooped up in a hotel room for days with absolutely nothing to do. My sole consolation was that I would be charging the client my daily rate.

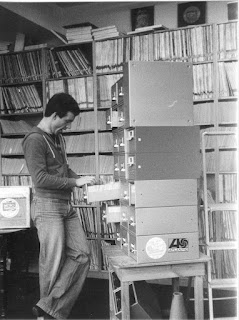

My task had been to interview each of the staff of tiny ‘Radio Juventus’ in Siófok to determine their role, their skills and their future potential. The station had been launched in 1989 by a local newspaper to serve German tourists who summered at Lake Balaton. It was about to be acquired by American public corporation Metromedia, owned by billionaire John Kluge [see blog], and I had been hired to discover precisely what he was buying and to plan its transformation into Hungary’s first national commercial radio station. I had completed a fortnight’s work when…

Three soldiers in military uniform suddenly burst into the underground bunker where I was installing computer programmes, talking loudly and waving around their guns. I was surprised but not initially alarmed as I knew they guarded the gate of the compound. Every day it took them ten minutes to inspect and approve my passport before they would let me enter. Maybe today they were simply bored. However, events quickly turned nasty when station staff translated the soldiers' demands into basic English:

“They say: 'you must go.' They say: 'go now and no stop.'”

Sorry? They mean me? But I work here! I am just doing my job! The staff were adamant. The soldiers had received orders. All foreigners (which meant only me) had to leave the compound immediately. I asked if I could telephone Metromedia’s office, a one-hour drive away in Budapest. While the soldiers glared at me, seemingly eager to make an arrest, the phone just rang and rang and rang. Where was the office secretary? In her absence, there was usually an answering machine on the end of the line. But now there was nothing.

I collected my belongings and the soldiers escorted me up the narrow stairs and out of the building. The bright sunlight made my eyes squint but the fresh air was invigorating. The bunker housing the radio station received no natural light, no fresh air and was always thick with cigarette smoke. Dust lay everywhere because it had served as an underground coal store during Soviet times. The soldiers stood in a line, holding their guns menacingly, and watched as I searched for my car keys. Above us loomed huge transmitter masts that the Soviets had built during the Cold War to jam broadcasts from West European radio stations. I drove the car slowly out of the compound and gave a friendly wave to the soldiers as I passed their checkpoint. They did not respond. In the rear-view mirror, I saw them lock the gates behind me and put down their guns. This must have been the most action they had seen in months.

An hour later, I was sat in the Budapest ‘office’ of Metromedia, in reality a converted bedroom within the Normafa Hotel owned by the Americans’ Hungarian business partner György Wossala. There was no sign of Bud Stiker, imported from Maine to manage this operation. No sign either of his harassed Hungarian secretary. I called Stiker’s mobile phone but it was switched off. The remainder of the afternoon, I stayed in the office but nobody came. The office phone rang regularly, which I had to ignore as I spoke no Hungarian. It had been a baffling day. I returned to my room, watched MTV and fell asleep to the sounds of loud revelry in the hotel grounds.

The next morning, I was eating breakfast in the hotel’s deserted dining room when Wossala appeared, so I asked if he knew what was happening with his American business partner. He was evasive and wanted only to talk about the wedding party that had hired his hotel the previous evening for a huge banquet and, when presented with their invoice, had drawn guns on his staff, then fled in their fleet of Mercedes.

“This is not good business,” he suggested to me.

I sat in the office again. Nothing happened until late afternoon when the secretary finally appeared, looking flustered. She had been trying to find Stiker the last two days, visiting downtown bars he was known to frequent.

“Everybody is looking for him,” she told me, “but he has just – pouf – disappeared.”

Stiker had worked for Metromedia in the 1980’s, managing radio stations in Colorado and Maryland. Prior to his arrival in Budapest, he had been executive vice president of Bonneville Broadcasting System, the US radio network owned by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I recognised that Stiker would understandably be unfamiliar with the European radio industry, probably the reason I had been hired as consultant. More puzzlingly, he appeared somewhat uninterested in visiting the business Metromedia was acquiring in Hungary, meeting the staff he was nominally managing, or creating a plan to transform the radio station … all of which was delegated to me, leaving him ‘hands off’.

Stiker’s mobile phone remained switched off and we found he had left no information about his whereabouts. The secretary checked with the hotel which confirmed he had not returned to his bedroom for two days. We were both totally confused.

The next day, the secretary arrived for work and told me she was quitting her job. She had checked her bank account and found that her wages had not been paid. Neither had the expenses she had rung up on behalf of Metromedia. I helped her carry the contents of her desk to her car outside. It did not seem to matter anymore whether the office items she was taking really belonged to her or to her former employer. I was on my own now and starting to get a little worried.

The next day, Wossala told me he was repossessing Metromedia’s office to convert back into a hotel room, despite the fact that I had observed no more than five guests staying in his hotel that mid-winter. He insisted I return the keys of the tiny Hungarian car I had been using to drive to the radio station, as he claimed it belonged to the hotel rather than Metromedia. That left me completely stranded.

My anxiety intensified the next morning when I found a hotel bill had been slipped under my door during the night, demanding I pay for my stay immediately, an expense that should have been taken care of by Metromedia. I told Wossala (truthfully) that I did not have sufficient funds to pay his bill, and neither could I change the date of my charter flight back to London, still several weeks away. The situation turned into a stalemate – he grudgingly let me continue my stay in his near-empty hotel, but now refused to serve me further meals.

I had to find food. I walked out of the hotel and turned left. There was nothing but a miniature railway, closed in winter, that would take hikers further into the forest hills. I walked back the opposite direction. About a mile from the hotel was a tiny roadside kiosk where I would point to dry biscuits, cola drinks and imported chocolate bars that I purchased with the limited amount of local currency I had previously changed. I had to eke out this basic diet the rest of the week.

Ten days after his disappearance, Bud Stiker suddenly re-emerged at the hotel. Amazingly, he had almost nothing to say about his sudden absence. He barely apologised for the inconvenience he had caused me and explained only that he had been “attending to important business” elsewhere. He said that there had been a “misunderstanding” between Metromedia and its Hungarian partner. I was more shocked by his lack of candour than I was by my treatment at the hands of the Hungarian soldiers ten days earlier. I half-heartedly completed my work and counted off the remaining days longingly until I could fly home.

Back in London, I wrote and submitted my report. Stiker queried my invoice, claiming I was overcharging because he believed the rate we had agreed was 'per month' rather than 'per week.' I found insulting his attempt to cut my fee by 75%, particularly after the experience I had just endured in Budapest. It seemed a bit rich coming from one of Metromedia’s old-timers whom my colleagues later alleged were being offered US$1,000,000 per year to manage one of its newly acquired stations in Europe as a kind of pre-retirement reward for earlier corporate loyalty (Metromedia had sold all of its 27 US radio stations by 1986). I resisted vociferously and was eventually paid in full. I hoped for more consulting work like this, though I wished Metromedia would not assign me to Stiker again … but it did.

That bleak winter month spent in a Budapest hotel room, watching ‘Nazi TV’, was the closest I had come to a war zone and the scary propaganda it produced.